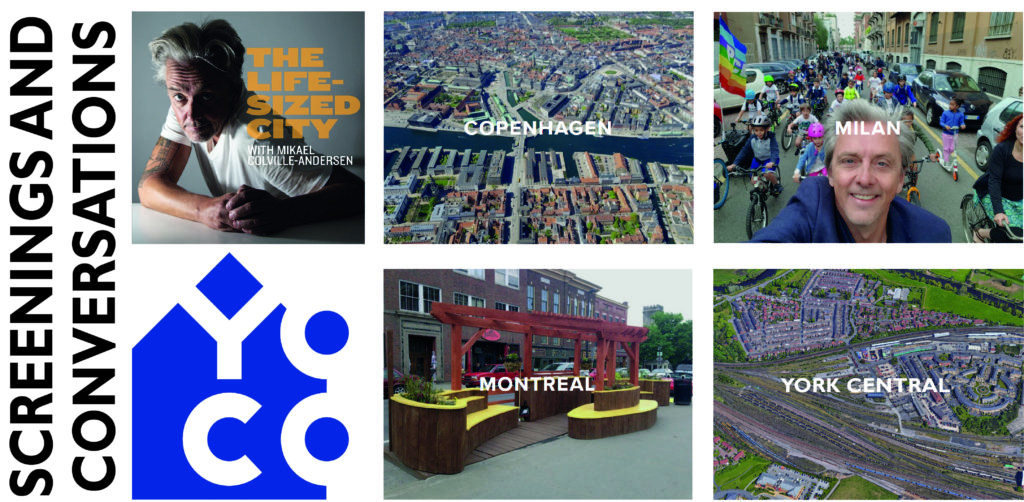

A response from Chris Bailey to our bonus screening of the Life Sized City visit to Medellin, Colombia

‘How is it that the pioneers of a new urban politics are always planting kale and rhubarb?’, asked architecture critic Justin McGuirk in a Guardian article in which he tackled the problem of ‘scaling up’ in urban development. Is being hyperlocal at odds with being properly strategic?

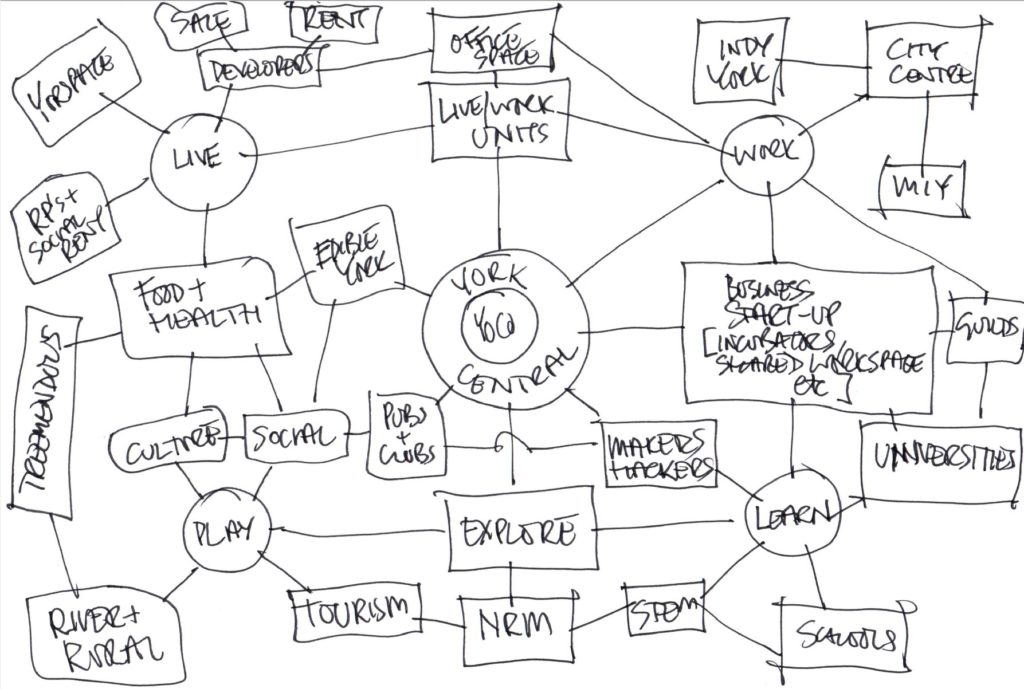

This challenge faces every community activist, and it defeats many. In York we often talk about better ‘connectedness’ being part of the solution, and that is true. Theory of Change workshops can help us identify connections and the wider conditions that contribute to, or are influenced by, your project. But, however valued they make participants feel, they often fall short of showing how pools of brilliance connect to form a grid, providing illumination across the city.

Seeing Mikael Colville Andersen’s Life-Sized City episode about Medellin for a second time drove home for me many of the lessons from the other cities, and from the panel discussion the previous week. It’s not just a case of life being better for some of the city’s population, in Medellin the worst of the nightmare era of civil war and gangsterism is over for all. Proving cause and effect in this field is impossible but there is general agreement that the decline in the murder rate from a high of 381 for every 100,000 inhabitants of Medellin, to just 20 per 100,000 in 2015, has much to do with the city’s decision to spend money on social programmes at neighbourhood level. There are still social problems of immense complexity to deal with, but if these are overcome, as the city’s Mayor declared many times, it is because the people have regained their self-respect.

The hard road to recovery began 25 years ago. In The Life-Sized City, we heard how, back then, the city government decided to devote 40% of the city’s budget to education and culture, with music and media making up the majority of projects, and with programmes taking place in every neighbourhood. In his book, Radical Cities, McGuirk devotes a chapter to Medellin, in which he attributes the transformation, not to education and the development of personal skills, but to innovative architectural design, and specifically to the stunning series of libraries and squares in barrios around the city. How do these approaches, one responding to need at the most local level, the other focused on complex capital projects, relate? In the context of Medellin and its revival, both are important, and neither is more important than the other.

Imagine that your child, brought up in the barrio, is just about to perform for the first time in one of the city’s superb community youth orchestras. The contribution made by the space, as an environment, not just for you, but for your family, friends and the community, is considerable. These distinct forms of benefit, social and cultural, interact to improve personal wellbeing. Urban change, which puts a contribution to wellbeing at its core, can be translated into action which is both strategic, and which responds to the individual character of each neighbourhood. In another, literally brilliant, example, Colville Andersen introduced us to Paza Luz (‘peaceful light’), in the Granizal neighbourhood high up in the hills. This was started by a telephone engineer, and spreads DIY street light to help people feel safer, with the additional benefit that the glow can also be seen from the wealthier city down below, making the barrio visible, and increasingly visitable.

York is one tenth the size of Medellin, and with less dramatic problems. Are the same ideas applicable? We’ve talked about what a fantasy Life Sized City episode about our city would include. I know if he was here 120 years ago Colville Andersen would certainly want to talk to local chocolate manufacturer, Joseph Rowntree, about his radical plan for a new settlement on the outskirts of decrepit, medieval/Georgian York.

Writing forty years before the Welfare State came fully into being, when public provision for the common good was regarded with suspicion, Joseph Rowntree said about his vision for New Earswick, that ‘I do not want to establish communities bearing the stamp of charity, but rather of rightly-ordered and self-governing communities’.

While ‘rightly ordered’ might sound paternalistic, it meant in practice providing opportunities for educational, physical and cultural development of citizens; the sports fields, the school and the remarkable Folk Hall. But ‘self-governing’ is the truly radical idea, requiring devolution to councils at local level. It reflects the spirit of the influential little book that so inspired Joseph and Seebohm Rowntree, Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow. When it first appeared it was entitled Tomorrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform, and it showed how the violent overthrow of the state can be avoided, by providing people with the means to manage their own lives.

This intensely practical little book, with its sensible proposals about reservoirs, was actually about how industrialisation, and the living conditions forced on working people in both town and country, were causing poverty, unemployment, illness and criminality. The key to the ‘social city’ of Howard’s vision is securing the land value for the benefit of the community, and setting up the means to govern it. This was not about maintaining the status quo. The goal was, ‘a stepping stone to a higher and better form of industrial life’.

If you see the same media headlines I do, then the current convergence of acute economic, social and cultural problems seems not so different from York in 1900, or even Medellin in 1990. Facing challenges on this scale, the veteran urban sociologist, Richard Sennett, sees the positive side of the response to the pandemic. In his essay in a recently published book, Everything Must Change! The World After COVID19, he identifies, within the popular movement to counter the virus, the spontaneous seeds of a new community spirit, ‘a localised sociability’ that can be encouraged by redesigning cities with the principle of decentralised ‘walking density’; recreating village-style communities that have all the amenities, from grocery stores to schools to gyms, allowing people ‘not to take public transport’. He even imagines Zoom could be de-privatised as a public good, using technology to ‘build solidarity’, crafting society anew from the bottom up.

Sennett, like others, sees dangers if we do not take the opportunity to ‘rekindle democracy’, by prescribing similar approaches, a respectful dialogue, as between equals, of civil society, private sector and government, such as enabled activists to turn commitments into reality in Colombia.

Back in 2009, Jorge Melguizo, who was then Secretary for Education and Culture in Medellin, reflected on this merging of local leadership and civic vision.

“They ask us what our ‘creative idea’ is. We answer it is not that much what we created, but rather what we believe in. In other words, our creativity lies in our commitments and in our passion for making our dreams come true. We believed it was possible to change our way of doing politics and governing the city. And we’ve made it happen through a civic movement – independent, made of people coming from NGOs, the civil society, the community organisations, the universities and the private corporations, with no experience whatsoever in politics. We won the last two elections against the traditional parties and everything they represented. We were told we were insane, but we believed it was possible. It took us five and a half years governing the second city of the country, putting budgetary focus on public education and culture. Once again we were told we would fail. We were told people expect their local governments to give immediate results, while culture and education pay off in the long term. We believed it was possible to offer short term results and the evidences of it are all around the city. Especially, it goes without saying, in the poorest areas, those recurrently abandoned by the State.”

We should accept that, unless we resort to violence, the alternative to politics is also politics. However different it may look, it is still about winning the right to decide how to use common resources for the common good. Solidarity is a craft, and rhubarb can lead to revolution!

Chris Bailey

22 February 2021

Links

Everything Must Change! The World After COVID19, https://www.orbooks.com/catalog/everything-must-change/

Justin McGuirk, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jun/15/urban-common-radical-community-gardens

Jorge Melguizo, https://creativecitysouth.org/blog-1/2018/3/29/medellin-a-creative-city

Paza Luz project, Medellin, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g6y-XxVVfbQ

Cormac Russell, Rekindling Democracy, http://rekindlingdemocracy.net/

Francois Matarasso https://parliamentofdreams.com/2020/05/21/the-road-to-reconstruction/

Justin McGuirk, Radical Cities, https://www.versobooks.com/books/2011-radical-cities