The second of the Screenings and Conversations took place on 13th Jan, drawing inspiration from Milan and the Life Sized City film presented by Mikael Colville-Anderson. This is a brief blog noting some of the issues which the film raised, and some of the discussion which followed.

Milan was in many ways a contrast with Copenhagen – a city with lots of heritage (Colville-Anderson imagines it as an operatic Diva) but also the remains of now-vanished industry, along with a location which makes it a focus for the movement of refugees. Oh – and streets full of Italian driving (and parking), too.

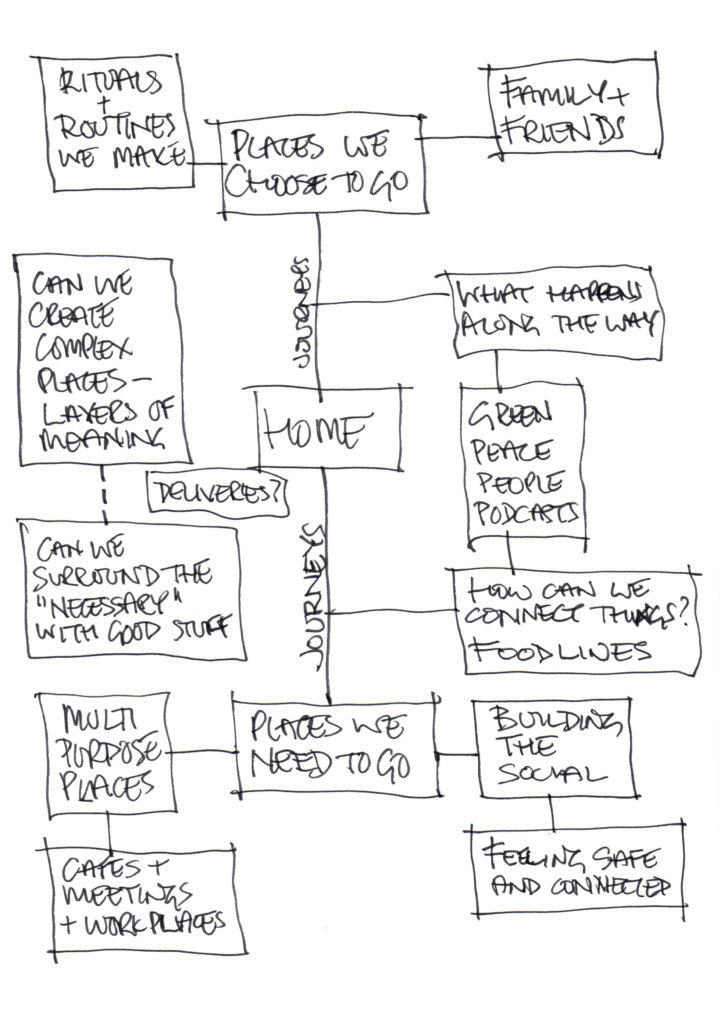

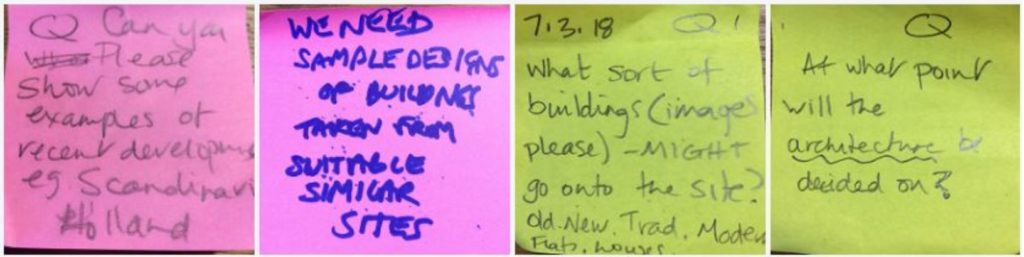

The initial picture was of a city of contrasts – new and old with a clear dividing line – where the new comprised massive gated developments designed by “Starchitects”. The argument was put forward that the old somehow “anchored” the new, although it became clear that behind this there was a substantial process of public engagement. The film looked at upcoming development on former railway land (we’ve been here before, folks) and the tension between upmarket development (an adjacent Prada office) and community wishes – for about 60% open space, 30% housing (including social housing) and intermediate social/cultural space. The local speaker touched on interesting ideas of how local communities needed to sometimes push things they didn’t want, as a way of enabling the greater plan – a subject we returned to in discussion afterwards in relation to protest and opposition.

There were a number of wonderful projects which worked with food as the fuel which drove them – the Recup food recycling project working in local markets (and oh, how many markets, too) to make available unwanted food, the Brektivists who came together from a Facebook project (initially a local discussion group which “went physical”) and turned into regular breakfasts in a roadside square – apparently in defiance of public regulation. And a community-run kitchen working with local refugee camps to put on meals – bringing together the food of a range of cultures along with understanding and dignity. Interestingly (for me anyway) all of these projects had a “founder” – none were municipally organised and all simply relied on someone – a local resident – making them happen. All raised questions – what makes good public space (does it even have to be publicly owned – or simply made available by a willing and imaginative host?) and – in our discussion afterwards – how do we shape thinking about new public space by developing the activities we want to share? And – now – how do we do this with ongoing restrictions on gathering due to Covid?

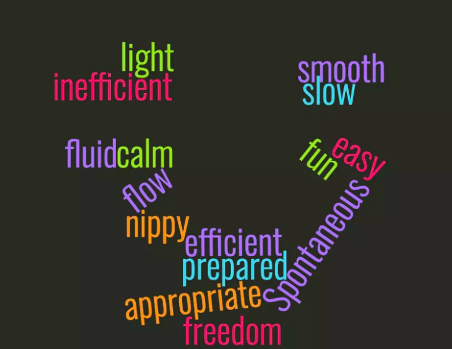

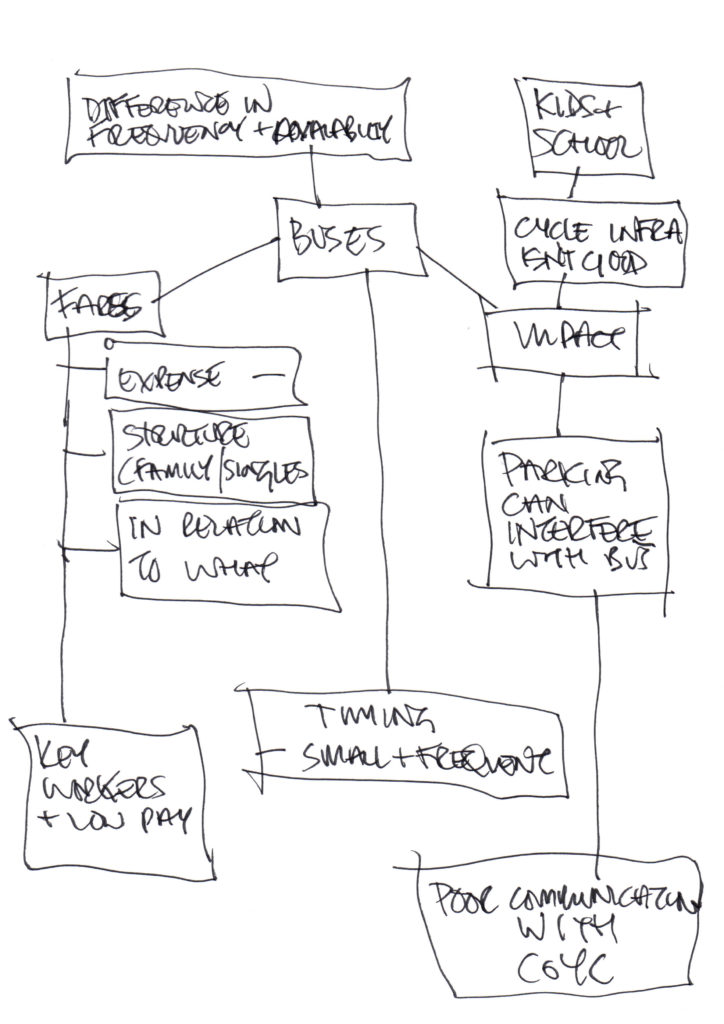

The subject of movement and cars was a recurring theme, as it was in Copenhagen. Milan historically had a network of canals, many of which were filled in to provide more road space, but where the city is now planning on opening up at least an initial 8km to re-connect waterways to the north (where there is flooding) and south (where agricultural land suffers drought). There was a lovely project called 12m2 where a group of people took over an urban square – astroturfing over the parking spaces to provide things which responded to local needs – bike repair, plants. They talked of meeting with local residents and a process of gentle discussion – an exchange, rather than “taking away”. We talked afterwards of the need to break down the tribalism that infects much UK (and York) discussion of movement and public realm – people being “drivers” or “cyclists” and reference to the Dutch mentality which is much more nuanced about this – bringing realism and humour.

All of which led to a personal favourite of the film – where a mother had got frustrated by the dangers of cycling her primary-school-age kids to school, so she joined with other parents, set up a gathering place and time, and organised (and piloted, with much shouting) a kind of kids’ Critical Mass ride to school, filling the road with smiling, pedalling kids. Just slightly chaotic – especially near the school gates – but probably less so than the cars of a typical UK school run. As we discussed afterwards, York has a proud history of filling the roads with cyclists (the carriageworks and chocolate factories) – can we revisit that?

Our next screening and conversation will visit Montreal on 20th January. Before then, please email or tweet us your comments to give us a starting point to build upon, and some key points to carry into the fourth session and our focus on York Central. Even better, write us a blog on some aspect of the film (or indeed this blog) that you’d like to respond to or pose questions around.