One of the recurring themes within public engagement is “how do you reach the hard-to-reach”.

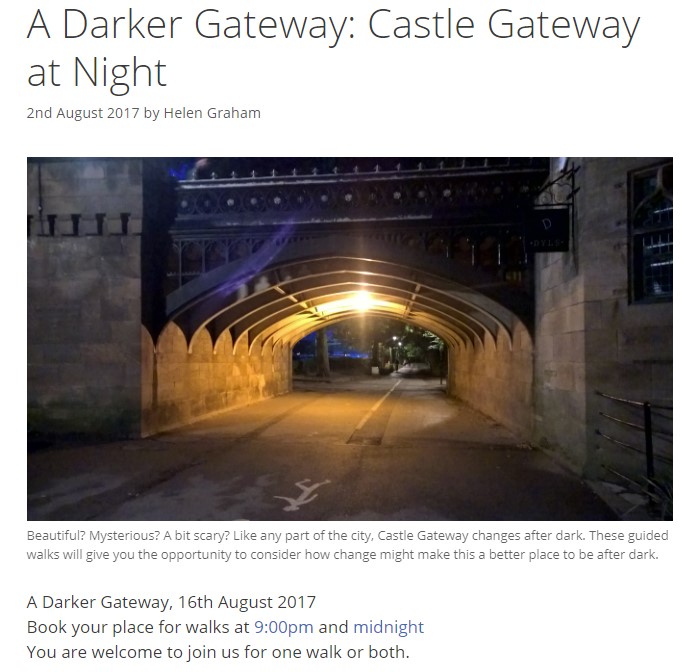

This merits a little unpicking straight away; There will be people who really do have a stake in a place or a question but who are often bypassed by “conventional” means of engagement – and here swapping “easy-to-ignore” for “hard-to-reach” is a fair criticism. With our work we’ve always been willing to work with the “usual suspects” but have also always made efforts to engage far more broadly – we’ve run appropriately-tailored sessions in church hall drop-ins, school classes, pay-as-you-feel cafes, midnight walks with the homeless – the harder to reach.

But there are still a lot of people out there beyond this. A big development – like York Central – feels like it should make ripples right through the city, but does it? Are there people who live in suburbs on the opposite side of York for whom it means little, who would argue it’s for someone else? I would argue that there are, and this then prompts reflection on the purpose both of the process of engagement and the subject itself – in this case York Central. How can we frame questions which engage both with the development proposals but also with the lives of everyone in the city? And how can the development be shaped to ensure it as generous as possible, bringing benefit to as wide a constituency as it can?

Ensuring that a process of engagement is agile enough to fulfil this broad range of purpose isn’t straightforward, and it can’t simply be extractive – it relies heavily on two-way communication which enables ideas to be identified and addressed within a conversation, bridging between fairly specific questions about the development – York Central – and everyday topics of conversation where the conversation is taking place – that largely unrelated suburb, for example. What connects the design of a street in York Central with “you said you’re looking forward to the weekend – what especially?”

Within our work, Helen and I talk often about citizenship and democracy, and particularly a type of distributed democracy which engages with everyday conversations in everyday settings. We have had conversations with people who work in the Local Area Coordinator (LAC) teams about the role of their work in big city-wide processes. We often look at how apparently specific decisions about – say, the design of a junction – actually connect with very broad policies around transport hierarchy and about personal experiences around, in that case, movement and travel.

Covid-19 and the response to it has added a layer of complexity to those everyday conversations; issues of loneliness or poverty may well have been heightened, and the opportunity to share and connect with others has been diminished. But is has also created opportunities – a call for volunteers brought over four thousand responses; an over-subscription which has meant many people who are happy to be involved in the city’s response to the virus have not been able to take part. For many people, thinking about the future might feel impossible due to uncertainty and fear, but there are many others who could – potentially – help kickstart a city-wide conversation linking their own neighbourhoods and offering collective reassurance, along with new networks connecting people with their neighbours.

So – what does all this have to do with York Central? What does York Central provide as a framework within such a broad conversation? It can be:-

- At the very least, the development is an idea, a “what if”, a tool for discussion around how we shape our city in future, what oft-misused words such as “sustainability” or “zero-carbon” really mean.

- It may be a future place where people might live or work – where there is a question “what would it need to be like for you to be there?”

- It may be a place of exchange – where people go to learn, or teach, or share – to be excited and challenged by it.

- It may be a place to go through – a new route into the city (with better buses or greener cycling routes. Or just less traffic).

- It may be seen as a catalyst for the city – a place where we pilot bold ideas which make broader change across the whole of York; where aspirations are deliberately set high because of the opportunities to test new futures.

There are routes we can use to connect these opportunities and questions back to that broader context. In our work to date we’ve used film-making terminology to talk about how you make use of an agile viewpoint – “panning” and “zooming”. Here, we need to be able to use:-

- Panning – to examine and understand existing neighbourhoods and use that understanding to shape York Central, the city centre, and those existing neighbourhoods themselves, and…

- Zooming – to use broad understanding to then shape detail decisions about specific places or issues.

Can we set up conversations which allow this to happen? We have the Local Area Coordination teams out there already, engaging with people at neighbourhood level, joining in their conversations and enabling them to be richer in purpose. We have thousands of Covid-19 volunteers, spread across the city and all, to some degree, already engaged with their own neighbourhoods. Can we – within whatever constraints on contact endure – start conversations which begin with simple questions:-

- What about your home makes you happy?

- What about your neighbourhood makes you happy?

- What about York makes you happy?

…but then start to allow us to pan and zoom in order to work with the stories which are generated, while at the same time ensuring that the conversations build connections within neighbourhoods, and start to identify opportunities for local collective action. Conversations – which start maybe by phone (an invite through the letterbox) and maybe continue via socially-distanced doorstep chats or tea in the street when that becomes possible – all facilitated by people who themselves live in that neighbourhood, who know some of its issues, and who will share some of their neighbours thoughts on what function York Central might play for them.

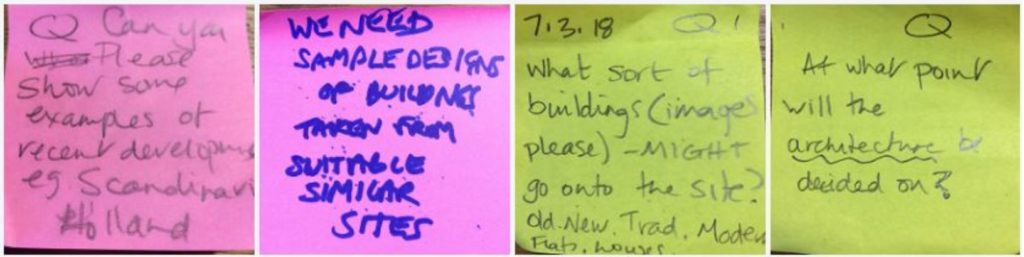

This could be a genuine process of imagining and re-imagining; of giving form to ideas around happiness and wellbeing, bridging between the solid piers of the lives of individuals in their neighbourhood, and the largest and most important new part of the city. It would add meaning to work on more specific York Central design issues too; conversations with interested groups and individuals have always identified broader issues, and this city-wide network of conversations would be a perfect way to take this process of “exploring the challenges” out to a much wider group of citizens, to create a richer democratic process which itself can lead to more broadly supported directions in policy and process.

“Active citizenship” – especially in a time of great change and amidst fears of disengagement with the democratic process – must be something we seek to bring out of the current crisis. York Central can be both a tool and a beneficiary if we have the courage to engage generously; to share, listen, and to then work within neighbourhoods to support people in creating better places, alongside York’s wonderful new quarter.